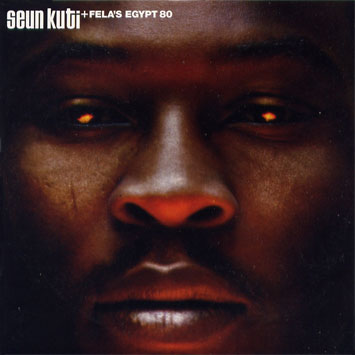

One of the best albums from the undisputed champion of afrobeat. If you don't have this, be sure to pick it up.

http://www.megaupload.com/?d=T4UZM3VZ

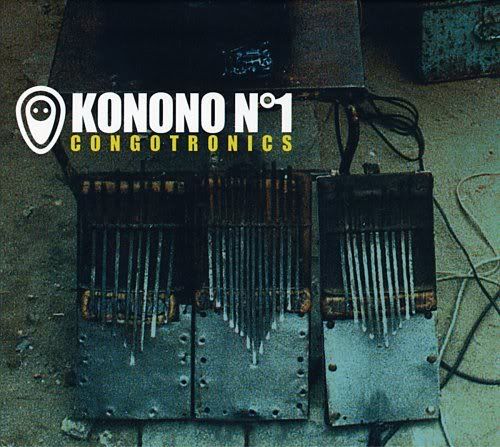

It is entirely possible that an amplified, slightly distorted likembe creates the most awesome sound on earth. There's no other sound quite like it, and there's no other band like Konono No. 1, the assemblage of Bazombo musicians, dancers, and singers from Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) that makes the likembe the center of their sound. It's something of an accidental update on Bazombo trance music, and it's thrillingly unique stuff, a torrent of kinetic sound that straddles the line between the traditional and the avant-garde. The likembe is commonly known in the West as a thumb piano, and there are variations of the instrument in different cultures across Africa-- perhaps the most well-known is the mbira, which is used across Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and parts of South Africa. The instrument has a pinging tone that is practically designed by nature to sound awesome with a bit of amp fuzz on it. Konono employ three electric likembes-- each in a different register-- and the amplification is very makeshift. The band formed in the 1980s to perform its traditional music, but soon found that being heard above the street noise of Kinshasa wasn't a going concern as long as they remained strictly acoustic. Scavenging magnets from car parts, they built their own microphones and pickups, and they augmented their percussion section with hi-hat and assorted scrap metal. Vocal amplification came from a megaphone, and the accidental distortion they drew from the likembes cemented their distinctive sound. Though their music is still traditional in style and content, recent trips to Europe have turned them on to how avant-garde what they're doing is, and they've fallen in with musicians like the Ex, Tortoise, and the Dead C.

It is entirely possible that an amplified, slightly distorted likembe creates the most awesome sound on earth. There's no other sound quite like it, and there's no other band like Konono No. 1, the assemblage of Bazombo musicians, dancers, and singers from Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) that makes the likembe the center of their sound. It's something of an accidental update on Bazombo trance music, and it's thrillingly unique stuff, a torrent of kinetic sound that straddles the line between the traditional and the avant-garde. The likembe is commonly known in the West as a thumb piano, and there are variations of the instrument in different cultures across Africa-- perhaps the most well-known is the mbira, which is used across Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and parts of South Africa. The instrument has a pinging tone that is practically designed by nature to sound awesome with a bit of amp fuzz on it. Konono employ three electric likembes-- each in a different register-- and the amplification is very makeshift. The band formed in the 1980s to perform its traditional music, but soon found that being heard above the street noise of Kinshasa wasn't a going concern as long as they remained strictly acoustic. Scavenging magnets from car parts, they built their own microphones and pickups, and they augmented their percussion section with hi-hat and assorted scrap metal. Vocal amplification came from a megaphone, and the accidental distortion they drew from the likembes cemented their distinctive sound. Though their music is still traditional in style and content, recent trips to Europe have turned them on to how avant-garde what they're doing is, and they've fallen in with musicians like the Ex, Tortoise, and the Dead C. They called him the "Sorcerer of the Guitar," and with his band, O.K. Jazz, he helped shaped not only the history of Congolese rumba, but also soukous. Franco was a giant, not just physically, but also in reputation, a guitar god every bit the equal of Hendrix or Clapton, but unknown in the West. This first U.S. compilation devoted to his work begins in the mid-1950s, when he was still a teenager, with "Merengue," and runs through 1987, and "Attention Na Sida," his final recording before dying of AIDS two years later. In between you get to understand his genius, not just as an instrumentalist, but also as a singer and writer, his band shading and filling out the music beautifully, while Franco himself produces flurries of notes and fluid runs that call to mind both Wes Montgomery and Ali Farka Toure. Compiled by biographer Graeme Ewens, these songs capture all the facets, from the brief catchy singles, the sizzling live magic, and the extended album tracks--and every one is vital. --Chris Nickson

They called him the "Sorcerer of the Guitar," and with his band, O.K. Jazz, he helped shaped not only the history of Congolese rumba, but also soukous. Franco was a giant, not just physically, but also in reputation, a guitar god every bit the equal of Hendrix or Clapton, but unknown in the West. This first U.S. compilation devoted to his work begins in the mid-1950s, when he was still a teenager, with "Merengue," and runs through 1987, and "Attention Na Sida," his final recording before dying of AIDS two years later. In between you get to understand his genius, not just as an instrumentalist, but also as a singer and writer, his band shading and filling out the music beautifully, while Franco himself produces flurries of notes and fluid runs that call to mind both Wes Montgomery and Ali Farka Toure. Compiled by biographer Graeme Ewens, these songs capture all the facets, from the brief catchy singles, the sizzling live magic, and the extended album tracks--and every one is vital. --Chris Nickson I'm going to be posting quite a few releases from the Ethiopiques series. I thought the best place to start is with this best of compilation.

I'm going to be posting quite a few releases from the Ethiopiques series. I thought the best place to start is with this best of compilation."A friend of mine was a stage manager for a theatre troupe who had been touring Africa and had bought an LP by Mahmoud Ahmed in a music shop in Addis Ababa. I was astonished - it seemed like some missing link of music. So I thought, 'What else is there?' Even though I knew nothing about Ethiopia or Ethiopian music, it seemed a good place to investigate. So I got on a plane to Addis the next month and invited Mahmoud Ahmed to tour."

Since then, much of Falceto's time has been spent on Ethiopian music. This month he was on tour again with Ahmed, who is at last being recognised as one of the world's great singers, this year winning a Radio 3 World Music Award. Since 1997, Falceto has produced a series of 21 fascinating compilations of Ethiopian music called Éthiopiques, of which a best-of selection is being released as a double album on Monday.

The series, always well-regarded, now seems to be breaking out of its cult following, with champions including Elvis Costello, who in the publicity material for the compilation suggests we investigate this "strange and wonderful" music.

British-based Indian singer Susheela Raman did a cover of a Mahmoud Ahmed song as the title track of her album Love Trap, and even has an "Ethiopian version" of Dylan's Like a Rolling Stone on her forthcoming album. But what propelled the music into chic drawing rooms more than anything else was the use of the enigmatic jazz of Mulatu Astatke in Jim Jarmusch's 2005 film Broken Flowers.

When Falceto first went to Ethiopia, in 1984, it was the year of famine and starvation. The country was governed by the Derg, a communist military junta that ruled from 1974 to 1987, which had imposed a curfew when took it power after Haile Selassie was ousted.

"Aside from the problems with the famine, the curfew and the censorship were very bad for the music and the nightlife," says Falceto. "I realised I had missed the great years of Ethiopian pop music."

Some musicians, such as Astatke, were drafted by the Derg in the 1970s to write stirring socialist-realist tunes celebrating the achievements of the revolution. Most of the releases in the Éthiopiques series are from what Falceto calls "the Golden Years" - the 1960s and early '70s, the dying years of Haile Selassie's regime.

The year of his visit was also the year of Live Aid, and Ahmed told me when I met him at the Radio 3 World Music Awards that he had shown Bob Geldof around Addis Ababa (Geldof has attracted considerable criticism for not using Ethiopian, or indeed African, musicians at Live Aid and Live 8).

Live Aid was, asserts Falceto, bad for the music of Ethiopia. "It created this cliché, which Ethiopians are mortified by, of the country as a kind of desert where everyone is dying of hunger. It's a mountainous country that is quite green - the problems in 1984 were more to do with geopolitical struggles in the Cold War than anything else. And Addis is a very sophisticated city, with plenty of rich people as well as poor."

Apart from its distinctive and rather oriental five-note scales, Falceto suggests that what makes Ethiopia so unique musically is the fact that "unlike any other African country, it has been independent for 3,000 years, apart from the six years the Italians were colonists." The only real outside influences in the 1950s and '60s were big-band music from the States, including Glen Miller, and later soul.

"Haile Selassie formed numerous brass bands for ceremonial purposes and they also played light music in the hotels," explains Falceto. "The result was something wild - the biggest stars sang in police and army bands. Mahmoud Ahmed was a member of the Imperial Bodyguard Band for years." Alemayehu Eshete, often dubbed "the Ethiopian James Brown", was the star vocalist with the Police Orchestra.

I meet Falceto in Toulouse, because he has finally found what he thinks is a world-class Ethiopian-style band in Les Tigres des Platanes, a French jazz group who he is recording alongside the Ethiopian chanteuse Etenesh Wassie. Something to celebrate along with the Ethiopian millennium this September - as the country uses the Coptic as opposed to the Gregorian calendar, it is still 1999 there.

As Falceto puts it, "It's a little behind the rest of us, but the world is finally discovering how great the music of Ethiopia is."